Britta Marakatt-Labba’s Moving the Needle

Sami artist, Britta Marakatt-Labba, campaigns for environmental protection and indigenous rights in Norway through the medium of embroidered landscapes and maps of epic beauty and subtle detail. The two hours I spent viewing a large retrospective of her work – ‘Moving the Needle’ – at the Nasjonal Museet in Oslo last weekend counts as my most enjoyable 2 hours wait for a hotel check-in. Sometimes delay really does generate pleasure.

Although I didn’t know what to expect from the exhibition, I was captivated by the first piece upon entering the cavernous hall of the newly constructed national gallery on Oslo’s harbour-front. ‘The Milky Way’ (above) evokes medieval ‘mappa mundis’, a stylised cartography that conveys history and legend as well as geography. Instead of continents, however, at the centre of Marakatt-Labba’s ‘Milky Way’ is a representation of our galaxy, with human-avatars assigned to stars. Around the circumference is a snapshot of Sami life: the spindly skeletons of trees in winter, an ocean brimming with fish, Sami on snowmobiles, in fishing boats, herding reindeer, colourful tipis standing out against the snow, and what I took to be a smudge of pollution infecting nature’s beauty.

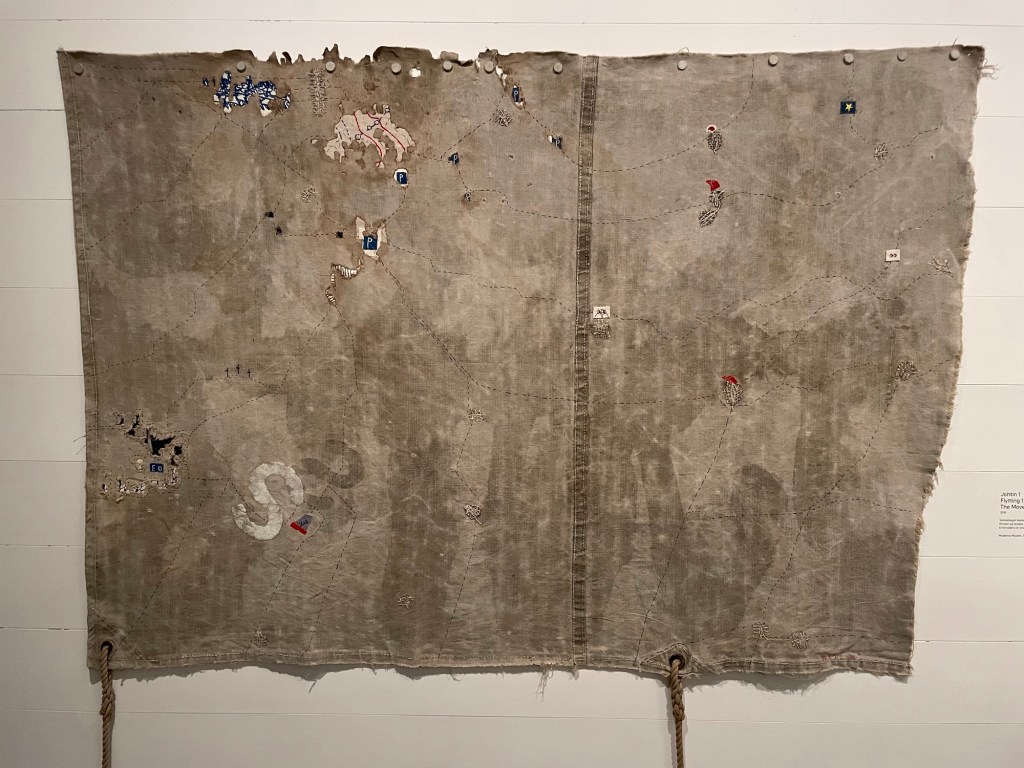

‘The Move’ uses a different kind of map and exudes a more military vibe. Using a battered piece of army tent as a canvas, Marakatt-Labba has embroidered the route of a forced human migration across the embroidered contour lines of Giron, the artists’ former hometown, which is now subsiding into the mines which extracted mineral wealth at a cost of habitation.

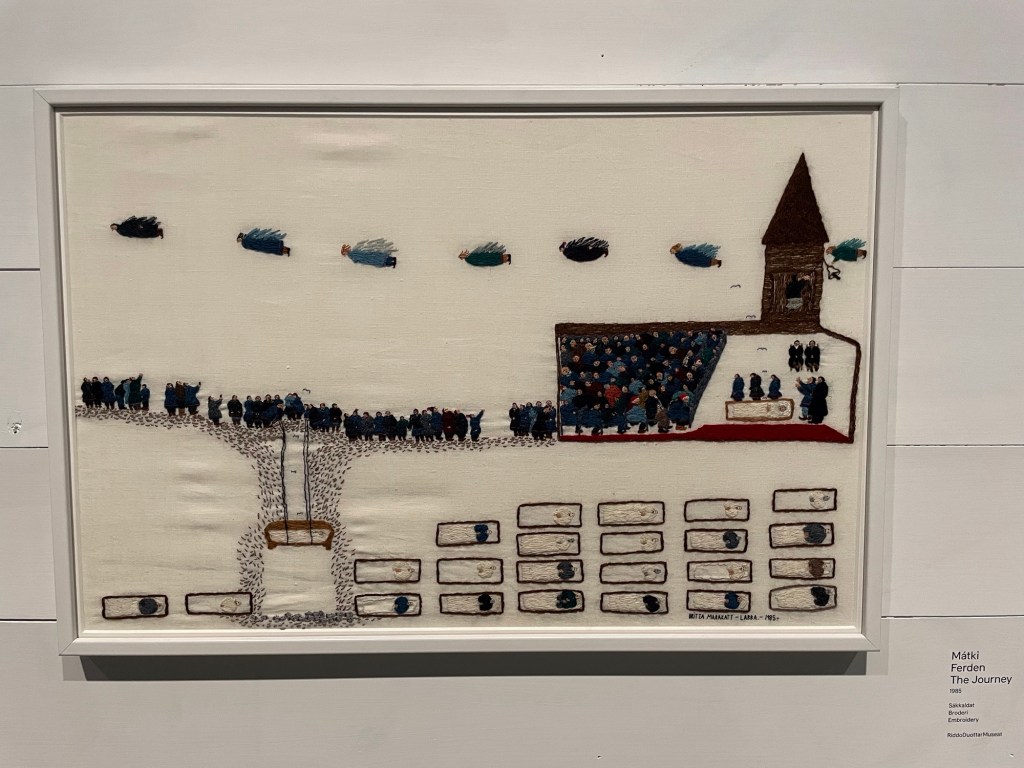

‘The Journey I and II’ chronicle a different type of move, from life to death. Mixing Christian religion and indigenous spiritual beliefs we see Sami communities honouring their dead in the churches of their colonial rulers (which are set on fire in other of Marakatt-Lubba’s pieces devoted to the Kautekeino uprising of 1852), but the continuum of connection between the living and ancestors is represented, I thought, in the images of the dead lying peacefully underground.

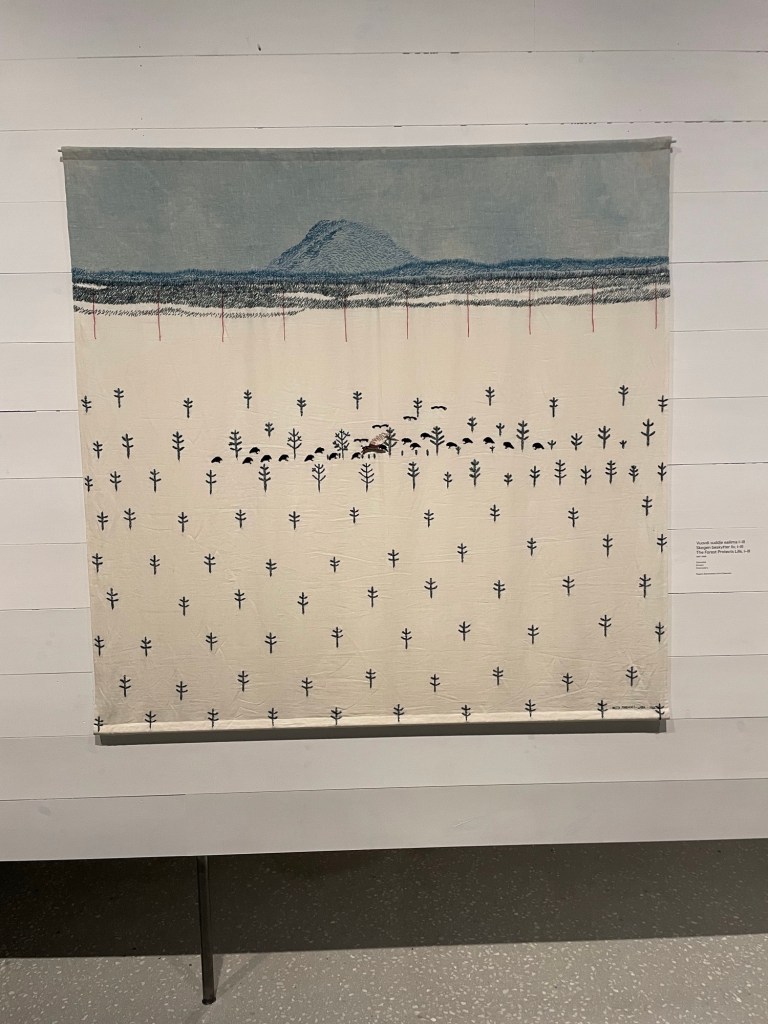

‘The Forest Protects Life’ triptych grimly shows the impact of human extractivism on the rest of nature. A woodland full of life in the first picture is reduced to a wasteland of tree-stumps in the second, amidst which a lone crow perches forlornly.

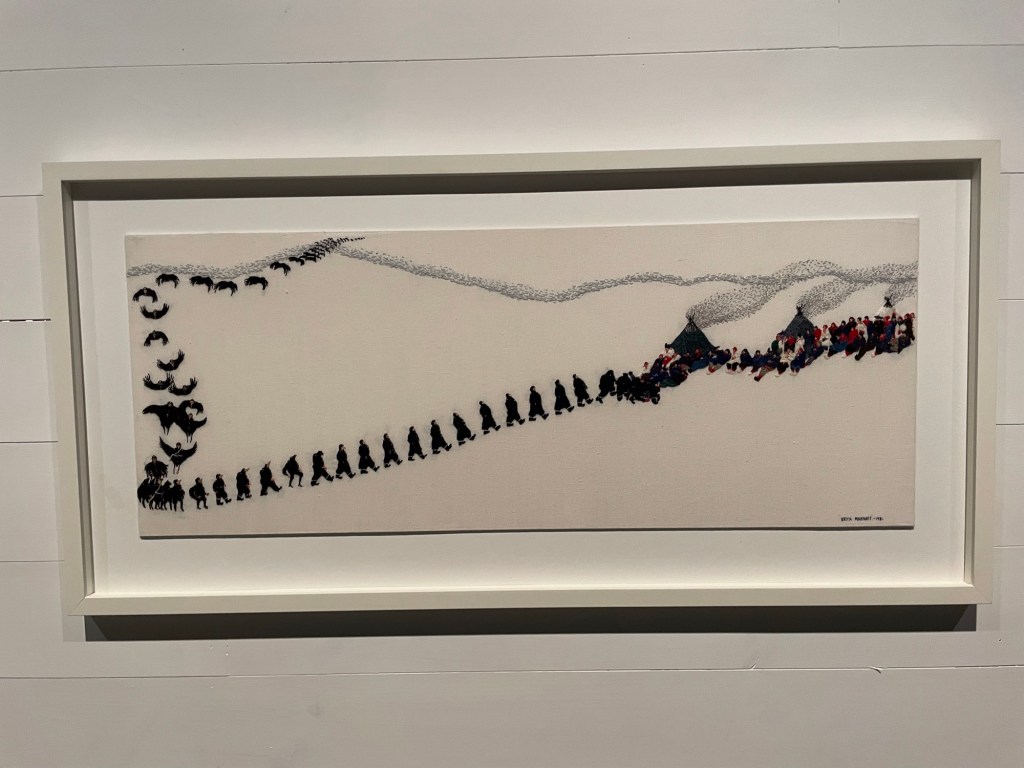

Marakatt-Labba has been involved in environmental and human rights campaigning since the 1980s. She seems to have formed a dim view of Norwegian law enforcement as a result. Police officers are depicted as corvids in ‘The Crow’, descending from the sky and then metamorphosising into human form, their black feathers becoming policy uniforms, as they march menacingly towards a peaceful protest of Sami women out on the snow. In ‘Flying Shaman’ the police fare even worse, herded like rats into the see by airborne noaidi (shaman).

There is a strong theme of the relationship between humans and the rest of nature throughout, and particularly between an ideology of capitalism and the indigenous philosophy that “we only take what we need and must not over consume”.

Elsewhere in this large and absorbing exhibition, I enjoyed ‘Spor’ (‘Tracks’), which in two parallel vertical strips of embroidered cloth depict first reindeer migration tracks crossing a railway line, and then a trail of star dust drifting from the heavens to the earth.

The figurative and literal centrepiece of the exhibition is the monumental ‘History’ – a 24 metre long continuous piece of embroidery detailing the myth, dream, and reality of Sami history. Housed in a rotunda, gallery visitors can follow its story from any starting point, I guess reflecting the non-linear appreciation of time in Sami culture. This is the Bayeaux Tapestry on an Arctic landscape and charting stargazers, hunters and protestors rather than military combatants.

It’s hard to look at Britta Marakatt-Labba’s work and not think about how painstaking the creative process must have been. The artist herself, however, sees this as a benefit: “Working with embroidery you have the time to think. With watercolours everything happens so fast. To me, it doesn’t matter if something takes time.” I am so glad she has, and continues, to find the time to make such beautiful and thought-provoking art.

- My listening accompaniment to ‘Moving the Needle’: North American indigenous singer, Samantha Crain’s ‘Pastime’

Leave a comment